International Fishing

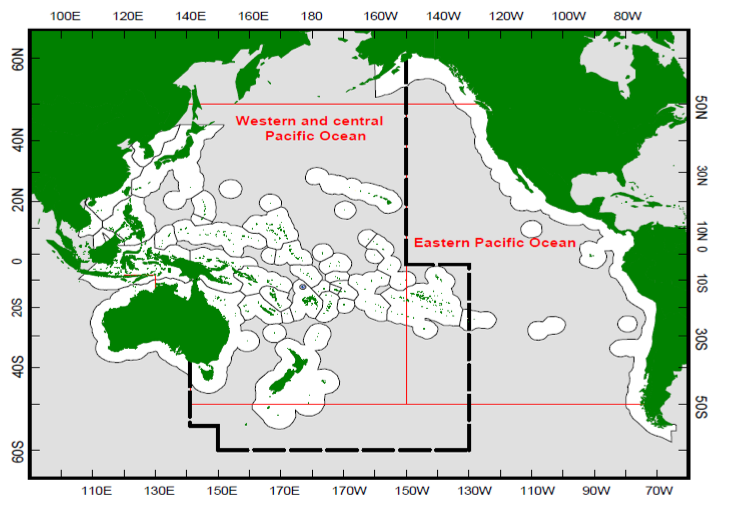

Map showing the areas of responsibility for the WCPFC and IATTC and shared jurisdiction. Source: Brouwer et al. 2015. Note: red lines delineate WCPO and EPO.

The ocean can be separated by two basic delineations: 1) the high seas or international waters and 2) waters under national jurisdiction. Similarly, nations can fall within one of two categories: 1) coastal States, which have geographic boundaries adjacent to the ocean, and 2) non-coastal States, which have no boundaries adjacent to the ocean. Since the early 1980s, the international legal framework has provided that coastal States possess sovereign rights and management responsibility over fishery resources within their 200 nautical mile (nm) exclusive economic zone (EEZ). In exercising their jurisdiction over their national waters, coastal States generally prohibit foreign fishing vessels from fishing with their EEZs unless specially authorized.

On the other hand, the high seas are subject to international management. Under international law all countries, including non-coastal States, have the right to fish on the high seas. Since the 1990s, however, high seas fisheries have been subject to more regulation by the international community. Generally, fisheries that occur in the high seas are subject to international management regimes developed by Regional Fisheries Management Organizations (RFMOs). For highly migratory species (HMS), such as tuna and billfish, which do not restrict themselves to political boundaries, international cooperation is essential to manage the stocks across their range. Generally, RFMOs serve to bridge the management gap between the EEZ and high seas regimes to ensure sustainability of transboundary fish stocks and consistency with the rights and obligations under international law provided to coastal States and States fishing on the high seas.

With regard to HMS fisheries management, the Pacific Ocean is divided into two large areas: the Western and Central Pacific Ocean (WCPO) and the Eastern Pacific Ocean (EPO). The longitudinal line separating the WCPO from the EPO is typically delineated at 150º W. The RFMO in the WCPO is the Western and Central Pacific Fisheries Commission (WCPFC) and the RFMO in the EPO is the Inter-American Tropical Tuna Commission (IATTC). However, there is an area of overlap, such that the WCPFC area encompasses waters east of 150º W to include French Polynesia (see map). In addition to the high seas of the WCPO, the area of the WCPFC also includes EEZs of coastal States, but generally national waters from 0-12 nm fall outside of the WCPFC management purview.