Northwestern Hawaiian Islands Fisheries

About

History of the Fisheries in the Northwestern Hawaiian Islands

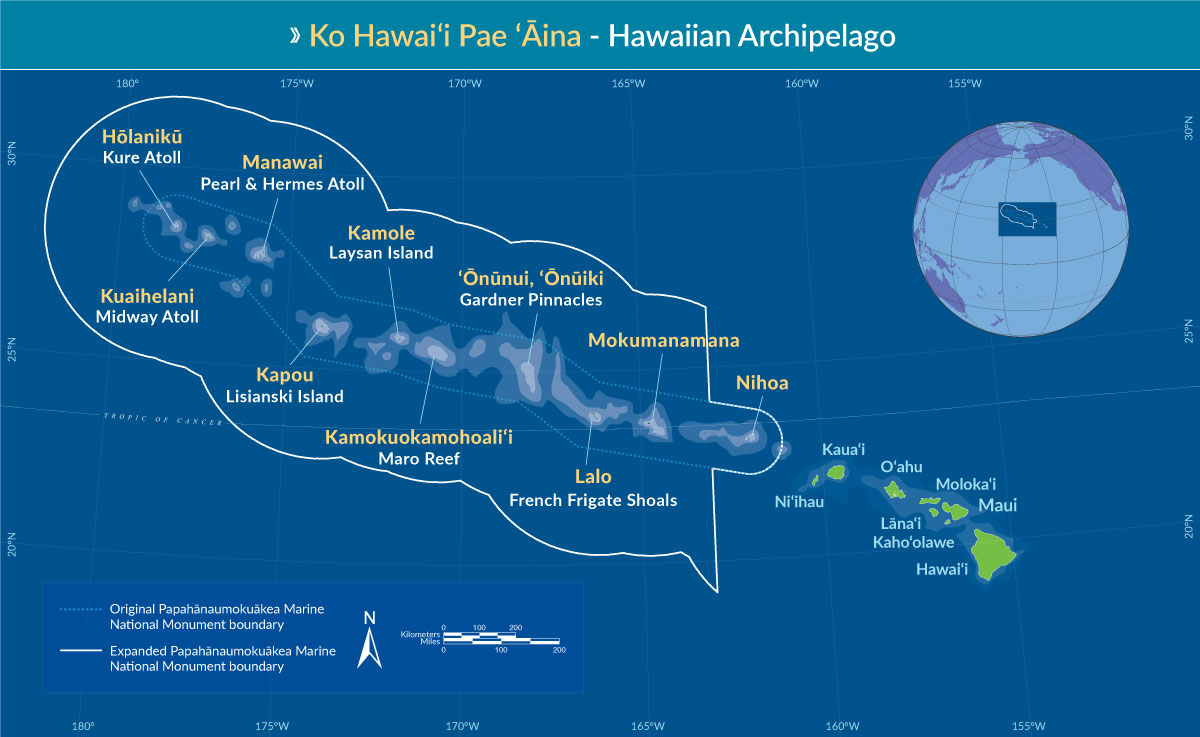

500–1500 AD Polynesians migrate to Hawaii. According to legend, the chiefess Pele and her family first land at Mokupapapa, a flat reef-like island, where her brother Kanenilohai is left. The next island is Nihoa, where her brothers Kaneapua and Kamohoalii (the shark god) are left. A study of Nihoa and Moku Manamana (Necker Island) in the 1920s uncovers numerous shrines and a fishhook of the type used with a kaka rig to fish in the kialoa (deep waters) for bottomfish. Carbon-dating indicates the islands were settled about 1000 AD.

1700s–1800s Native Hawaiians from Kauai and Niihau make regular canoe trips to Mokupapapa, an island west of Kaula, for turtles and seabirds. Nihoa is occupied each summer by Native Hawaiians until the late 1800s. Olona fiber fishing lines of 300-foot length suggest bottomfish fishing took place as several of the lines could be tied together.

Read More

1910–40s In 1917, public officials deny requests to establish a fishing station and cannery at French Frigate Shoals (FFS). Daikoku Maru nets inshore species in the shoal until it is lost at sea in the 1920s. In the 1930s, Katsuren Maru fishes for inshore species and turtles as far as Maro Reef and Lanikai and Islander fish throughout the NWHI for pearl oysters, ulua, mullet, weke, akule, lobster from the reefs and shoals and onaga, uku, ehu, opakapaka and hapuupuu from the deep seas. Lanikai establishes a fishing station at Pearl and Hermes Reef. Reliable nets inshore species and captures turtles in the mid 1940s. Simba is a mothership for three to four smaller sampans fishing for akule, moi, weke, lobsters, turtles and other inshore species. Capt. Jake Hoapai and 11 crewmembers are lost at sea in the late 1940s.

1940–44 World War II leads to the development of a US Navy base at Midway Atoll. At FFS, the 11-acre Tern Island is converted into a 42-acre naval airstrip. A Coast Guard LORAN station is established at East Island, FFS.

1946–59 Nine large commercial vessels fish the NWHI. By 1946, two fishing bases at Tern Island airship trapped fish and turtles to Honolulu. The Pacific Oceanic Fishery Investigation in 1948 begins research of potential commercial fishery yield. In 1950, Leo Ohai, owner and captain of Sea Queen, transports a small aircraft to FFS to support akule fishing and Buzzy Agard flies catches in a DC-3 cargo aircraft from FFS to Honolulu and captains Koyo Maru to catch akule at Nihoa. Sea Hawk and Osprey fish Lisianski for shoal and deep-sea species. Osprey is lost at sea in the 1950s. All hands are rescued off FFS. Elaine and Brothers fish for lobster and inshore species at FFS. Koyo Maru fishes for deep-sea and inshore, shoal species and is lost at sea in the 1960s. Kaku fishes to Maro Reef for shoal and deep-sea species. Taihei Maru fishes to Lisianski for ulua from the shoals and onaga, opakapaka and other species from the deep. A limited local market causes the fishery to eventually decline.

1964 Wilderness Act is passed, prohibiting commercial enterprise within a National Wilderness Preservation System. NWHI is twice proposed to Congress as a wilderness area, but the State of Hawaii strongly opposes any prohibition of commercial fishing.

1965–77 Japanese longliners annually expend up to 2,170 vessel days in the NWHI, harvesting up to 2,204 mt of tuna and 1,260 mt of billfish. Japanese pole-and-line vessels targeting skipjack tuna, Japanese draggers for precious corals and Japanese and Soviet trawlers targeting groundfish are observed in NWHI waters. A Governor’s Task Force recognizes that fishery resources on the main islands are taxed and recommends developing NWHI fisheries. An expanded local market causes NWHI bottomfish and troll landings to increase. In 1973, National Marine Fisheries Service (NMFS) begins NWHI reconnaissance cruises. In 1976, Congress adopts the Magnuson Fishery Conservation and Management Act, establishing the Western Pacific Fishery Management Council to manage fisheries in federal waters around Hawaii and other US Pacific Islands. Foreign vessels are forced from NWHI waters.

1978 Following a Governor’s Advisory Committee recommendation, NMFS, US Fish and Wildlife Service, State of Hawaii and University of Hawaii begin a five-year cooperative research program to identify NWHI marine resources.

1980–86 The Council establishes the Precious Coral Fishery Management Plan (1980), Crustaceans FMP (1983) and Bottomfish and Seamount Groundfish FMP (1986). A Crustaceans FMP amendment creates no-take zones 20 nmi around Laysan and landward of the 10-fathom curve in all other NWHI areas.

1987–91 The Council establishes the Pelagics FMP (1987), NWHI Hoomalu Zone bottomfish limited entry program (1989) and Protected Species Zone, 50 nm around NWHI, within which longline fishing is prohibited (1991).

1995–2000 Council contractors complete Review of coral reefs around American Flag Pacific Islands and assessment of need, value and feasibility of establishing a coral reef fishery management plan for the Western Pacific Region (1995) and An assessment of the status of coral reef resources, and their patterns of use, in the US Pacific Islands (1997). The NWHI Mau Zone limited entry program is established (1999). Following public scoping hearings, the Council submits the draft Coral Reef Ecosystem FMP and preliminary draft EIS to NMFS. Preferred alternatives identify all federal waters 0–50 fathoms in the NWHI as marine protected areas and recommend 24 percent of the total NWHI as no-take zones.

2005 September 29, 2005: The State of Hawaii Governor Linda Lingle signs regulations establishing the Northwestern Hawaiian Islands Marine Refuge. The Refuge includes all state waters of the NWHI extending 3nm seaward from any coastline.

2006 June 15, 2006: President Bush created the NWHI Marine National Monument on top of the footprint of President Clinton’s NWHI Coral Reef Ecosystem Reserve using the Antiquities Act. Under the act, public process, Congressional action and scientific justification are explicitly not required. Presidential Proclamation 8031 (71 FR 36443).

2007 February 28, 2007: President Bush issues Presidential Proclamation 8112 amending Proclamation 8031 of June 15, 2006 to read “establishment of the Papahānaumokuākea Marine National Monument”; amends Additional findings for Native Hawaiian Practice Permits, 2(e), to read: Any living monument resource harvested from the monument will be consumed or utilized in the monument.

2016 August 25, 2016: President Obama issues Presidential Proclamation 9478 entitled, Papahānaumokuākea Marine National Monument Expansion creating a second Marine National Monument in the region, adjacent to the PMNM and out to the full 200nm EEZ westward from the 163◦ West Longitude.

2020 Congress includes language in the 2021 Appropriations Bill: “Papahānaumokuākea Sanctuary Designation.—The Committee directs NOAA to initiate the process under the National Marine Sanctuaries Act (16 U.S.C. 1431 et seq.) to designate the Papahānaumokuākea Marine National Monument as a National Marine Sanctuary to supplement and complement, rather than supplant, existing authorities. NOAA shall provide the Committee an update on this designation before the end of fiscal year 2021.”

2021 November 19, 2021: Office of National Marine Sanctuaries requests fishing recommendations for the Monument Expansion Area of the Northwestern Hawaiian Islands in preparation for the designation of a National Marine Sanctuary for the area. Under the National Marine Sanctuaries Act section 304(a)(5), the Council is provided the opportunity to provide fishery regulations for the sanctuary.

2023 April 14, 2023: The Council transmits final recommendations for fishing regulations to the National Ocean Service, including prohibition on commercial fishing and federal permitting and reporting requirements for non-commercial fishing and Native Hawaiian subsistence fishing activities.

Scientific & Economic Value

The NWHI accounts for two-thirds of the U.S. EEZ around Hawaii and 83% of its coral reef habitat. The region has been productive fishing grounds for Hawaii’s fishers since pre-contact with Western societies. Commercial fishing occurred there as early as 1917.

The sustainable NWHI bottomfish fishery harvested healthy stocks of red and pink snappers. These fish are featured dishes in the Hawaii regional cuisine, which local restaurants cater to tourists and residents. These red fish hold special significance to the people of Hawaii, particularly at New Years. When open to commerce, nearly half of the bottomfish and most of the lobster that was commercially harvested annually in Hawaii came from the NWHI (annual landed values from the NWHI were ~$1 million and ~$1.2 million, respectively). The 2006 designation of Papahanaumokuakea Marine National Monument phased out commercial fishing in the region. For more details, see “The Unintended Consequences,” a Council presentation for Washington, D.C. officials that provides an analysis of fishery impacts.

Research to assess NWHI resources was initiated in the late 1970s as part of a Tripartite Cooperative Agreement between the National Marine Fisheries Service (NMFS), the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service and the Hawaii Division of Aquatic Resources. This agreement concluded in the early 1980s, but not before several symposia were held to exchange research results and ideas. Key management products of the first two symposia were fishery management plans for bottomfish, crustaceans and precious corals. Another valuable product of these investigations was a first of its kind Fishery Atlas of the NWHI (1986).

Members of the Council’s Scientific and Statistical Committee contributed to continued research and understanding of the NWHI. View a collection of published papers (2006).

The NWHI hosts a diversity of protected species, including Hawaiian green sea turtles and monk seals, and seabirds. The Council implemented management measures starting in the 1980s to minimize fishery impacts to protected species. These measures include trap gear design specifications and a net prohibition for the lobster fishery, a drift gillnet ban, federal observer programs in the NWHI bottomfish and Hawaii longline fisheries, and a 50-nautical-mile protected species zone around the NWHI that prohibited longline fishing in 1991.

Pelagic fisheries targeting tuna and swordfish that historically utilized the U.S. EEZ around the NWHI are valued between $100 to $115 million per year. Most of these operated seaward from 50 nautical miles (nm). A 2020 study by scientists at NMFS found that prohibitions in fishing seaward from 50 nm (expansion of the Papahanaumokuakea Marine National Monument) reduced fishery performance of longline vessels that had used these waters by 7% and revenues by 9%, with economic losses of $3.5 million in months following this prohibition [Chan 2020].

- Chan, Hing Ling. “Economic impacts of Papahānaumokuākea Marine National Monument expansion on the Hawaii longline fishery.” Marine Policy. 14 Feb. 2020.

- Protected Species Conservation Monograph, 2016

- For more information, see the following pages on the Council website: Protected Species, Bottomfish Fishery Management Plan, Coral Reef Ecosystem Fishery Management Plan, and Area-Based Management Tools.

Cultural Importance

The Northwestern Hawaiian Islands (NWHI) are often cited as the first place that Pele and her family landed in Hawaii. Everywhere she goes, she is pursued by her sister, Namakaokahai, and forced to flee until eventually settling on Hawaii Island, her current residence. These traditions recount the geological formation of the islands and in order of the hotspot prior to modern science identifying these phenomena. It also provides the migration route for Polynesians that came to Hawaii. Carbon dating of artifacts left in the NWHI confirms settlement at about 1000 AD. Mokumanamana and Nihoa were the focus of ritual use and human occupation continually from 1400 to 1815 AD, with intermittent use well into the 19th century.

Much of the information about the cultural importance of the NWHI is recorded in oral histories and genealogies that note the continual use of the islands by the people of Hawaii. Regular trips by canoe were made to the NWHI for fishing, sea turtles, and seabirds up until the 1800s. Upon arrival of western sailing ships that exploited the area, the alii recognized the importance of the NWHI with the Queens and Kings politically annexing the islands into the Kingdom.

Today, the cultural importance is being rediscovered as archeological and ethnological research have identified important areas for traditional navigation, resource collection, and use of the islands. For more on the cultural significance of the NWHI, see the Office of Hawaiian Affairs website.

Here are examples of how native Hawaiian culture and traditions are being reincorporated into management and governance in Hawaii.

- Aha Moku – Beginning in August 2006, the Council hosted the Puwalu series to engage the Hawaiian community to bring native practitioners from across the 43 moku (regions) together to discuss traditional practices and advise the Council’s Hawaii Archipelago Fishery Ecosystem Plan. Through the combined efforts of more than 100 kupuna and Native Hawaiian resource practitioners in the State of Hawaii, Governors Lingle and Abercrombie signed Act 212 and 288 into law in 2007 and 2012, respectively. These Acts initiated the process to instill best practices upon indigenous resource management of moku boundaries and established the Aha Moku Advisory Committee.

- Office of Hawaiian Affairs Mai Ka Po Mai, 2021 – Mai Ka Po Mai is a culmination of more than 10 years of discussions with the Native Hawaiian community and the managing agencies to provide a Native Hawaiian perspective into Papahānaumokuākea management. The guidance document uses traditional concepts and cultural traditions related to Papahānaumokuākea in its structure to set a foundation for how management should be conducted.

Northwestern Hawaiian Islands Proposed Sanctuary Fishery Regulations FAQs

Why is a Sanctuary being proposed now?

The Office of National Marine Sanctuaries (ONMS) has long desired a National Marine Sanctuary for the NWHI (https://www.papahanaumokuakea.gov/sanctuary-designation). A previous attempt in 2000 that was directed by President Clinton was eclipsed by the last-minute designation of a Marine National Monument by President Bush in 2006 under the authority of the Antiquities Act. Given the recent example of Presidents altering existing monuments through the Antiquities Act, there is a desire to create more permanence in the region and there has been a recent push to designate the sanctuary through direction provided by President Obama’s Presidential Proclamation 9478 that designated the Monument Expansion Area as well as a provision put into the 2021 Appropriations Bill to designate the NWHI as a National Marine Sanctuary.

Which boundary options are ONMS considering?

It is unclear at this time. The Council understands that the sanctuary designation process, which includes an Environmental Impact Statement analysis to satisfy the National Environmental Protection Act and formal public scoping, will examine boundary options.

What is the role of the Council?

Under the National Marine Sanctuaries Act section 304(a)(5), ONMS works with the Council to assess and determine the need for fishery regulations to meet the goals and objectives of the sanctuary. The Council can either recommend fishing regulations, recommend that fishing regulations are not necessary, or decline to act. The Secretary of Commerce may develop fishing regulations in the event that the Council proposes regulations that do not meet the goals and objectives of the sanctuary, refuses to recommend regulations, or fails to act in a timely manner.

What does that mean for fishing in the NWHI?

The Council initially placed a protected species zone in the NWHI that prohibited longline fishing within 50 miles. Also in place in that area were fishery regulations for lobsters, precious corals, and bottomfish that were put into place in the 1980s. In 2000, a Coral Reef Ecosystem Reserve was placed over that same area that prohibited fishing on coral reef fisheries as well. The establishment of the Papahānaumokuākea Marine National Monument phased out fishing in the 0-50 mile zone and currently only subsistence/sustenance fishing is allowed. In the area outside of 50 miles to the 200 mile extent of the US Exclusive Economic Zone (the Monument Expansion Area , or MEA), commercial fishing is prohibited by Presidential Proclamation 9478 but non-commercial fishing and Native Hawaiian subsistence fishing can be allowed as a regulated activity. This is the fishing that the Council has provided recommendations on for fishing regulations in the MEA.

Does the Council see this as a way to reopen the NWHI to commercial fishing?

Commercial fishing is prohibited in the NWHI. The Council will continue to look for ways to support non-commercial and subsistence fishing, remaining consistent with the proclamations.

Can fish come home to the Main Hawaiian Islands?

The Council has evaluated options for permitting the limited, non-commercial use of fish harvested within certain areas of the monuments, which may include the transport, consumption and sharing of fish outside the monument.

NOAA Request for Comments on Proposed Sanctuary designation

The National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA), in cooperation with the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service (USFWS), the State of Hawai’i, and the Office of Hawaiian Affairs (OHA), is initiating the process to consider designating marine portions of Papahānaumokuākea Marine National Monument as a national marine sanctuary.

NOAA requested comments on the following topics. Click here to see the list of public comments.

The proposed designation of marine waters of the Monument as a national marine sanctuary, including the spatial extent of the proposed sanctuary and boundary alternatives NOAA should consider:

- the location, nature, and value of resources that would be protected by a sanctuary;

- management measures for the sanctuary and any additional regulations that should be added under the NMSA authority to protect Monument resources;

- the potential socioeconomic, cultural, and biological impacts of sanctuary designation;

- information regarding historic properties in the entire Monument area and the potential effects to those historic properties to support National Historic Preservation Act compliance under section 106; and

- other information relevant to the designation and management of a national marine sanctuary.

At the March 2022 meeting, the Council decided that draft fishery regulations will be necessary as part of the proposed sanctuary designation.

For additional information, please visit the proposed sanctuary’s website.

Public Meetings on NWHI Monument Expansion Area Fishing Regulations held in November 2022

Meeting Agenda

Federal Register Notice

Background paper on NWHI MEA Fishing Regulations

Meeting Flyer

Final Summary Report of NWHI Fishing Regulation Public Informational Meetings