Guam (Mariana Archipelago)

Fishing is central to life in the Mariana Archipelago—supporting food security, cultural practice, recreation, and tourism.

This page provides a snapshot of Guam’s fisheries, current management, and annual reporting, with links to key plans, projects, and ongoing issues. For cultural context and traditional knowledge, see the Indigenous Resources section below.

Overview

The U.S. Territory of Guam is located on the other side of the dateline from the rest of the United States in the part of Oceania known as Micronesia. Guam is more closely related in heritage and tradition to other Micronesian archipelagos than to the United States. Guam and neighboring US Commonwealth of the Northern Mariana Islands (CNMI) shared a common geography, political status, history, culture and economy until 1898, when the archipelago was politically divided.

Archaeological research indicates fishing in the Mariana Archipelago dates back roughly three millennia. Colonial periods under Spain, Japan, and the United States reshaped fishing activity and contributed to the mix of shore- and boat-based fisheries seen today.

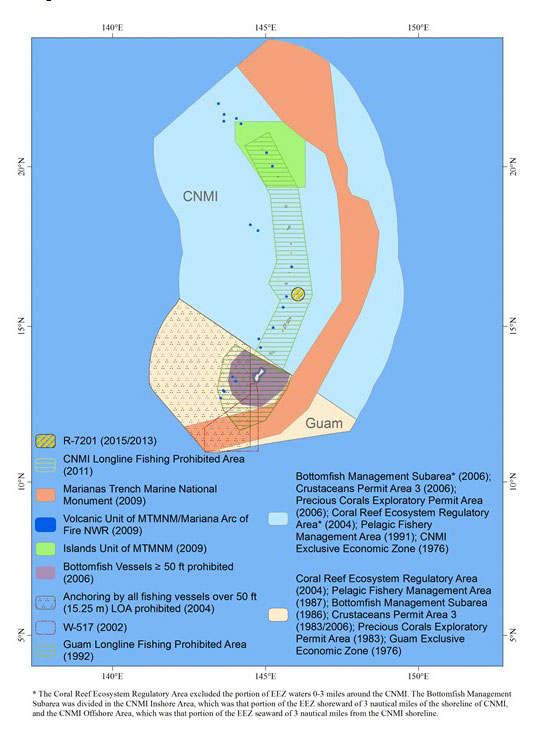

In Guam, waters 0 to 3 nautical miles from shore are managed by the Territory and waters from 3 to 200 nautical miles offshore (within the U.S. exclusive economic zone) are federally managed. Enforcement of federal fishery regulations is handled through a joint federal-territorial partnership.

Guam Fisheries

Guam’s fisheries include small-scale troll, bottomfish, and coral reef fisheries, with landings sold locally as well as used for subsistence and cultural sharing. Fishing occurs from shore and small boats.

The U.S. EEZ around Guam is extensive and includes underutilized pelagic and bottomfish resources.

The Council publishes annual fisheries updates in its Fishery Ecosystem Plan Annual Reports, drawing on data collected in partnership with territorial and federal agencies.

Pelagic Fisheries

The pelagic fishery on Guam is made up mostly of small trolling boats that fish mainly in the U.S. EEZ around Guam, and at times around the CNMI. The fishery primarily targets mahimahi, wahoo, skipjack/bonita, yellowfin tuna, and Pacific blue marlin.

An estimated 447 boats participated in Guam’s pelagic fishery in 2024, similar to 2023. Total pelagic landings in 2024 were 699,120 lbs, a 2.7% decrease from the previous year. Tuna Pelagic Management Unit Species (PMUS) landings were 456,156 lbs (down ~23%), while non-tuna PMUS landings were 237,040 lbs (up 105%).

In 2024, fishers were asked about shark interactions during boat-based interviews. Of 466 interviews, 195 reported shark interactions (42%). The interactions were primarily depredation events—sharks consuming hooked fish before retrieval—resulting in lost catch and occasional gear damage for small-boat fishers. Fishers described depredation as persistent (and in some cases increasing), particularly during pelagic trolling trips targeting species such as yellowfin tuna and mahimahi; some reports noted repeated strikes on the same fish and sharks lingering around vessels. Based on these interviews, interactions were generally economic/operational challenges rather than bycatch concerns, and no incidental hooking or take of protected sharks was reported.

Island Fisheries

Bottomfish

The bottomfish fishery on Guam includes recreational, subsistence/cultural, and small-scale commercial fishing. Most bottomfishing occurs on offshore banks, but information on reef conditions in these areas is limited. Guam’s fishery targets a multi-species complex known as Bottomfish Management Unit Species (BMUS)—about 13 deep-water snappers, groupers, and related species—primarily caught with handlines.

A 2019 scientific review found Guam’s BMUS stocks were overfished, but overfishing was not occurring at that time. The Council recommended a rebuilding plan for the fishery that started in 2022 with an annual catch limit of 31,000 pounds, and included safeguards to keep catches from going over the limit.

A 2024 update showed the stock has improved, likely helped by lower catches from 2017–2020. The review found BMUS is likely no longer overfished and likely not experiencing overfishing, but the fishery has not fully rebuilt yet. The Council has also discussed possible tweaks to the plan—such as keeping the limit the same or raising it slightly—while still aiming for long-term recovery.

Overall, the stock shows signs of improvement from conservation measures, but remains managed conservatively due to data limitations, variability in catches/CPUE, and the multi-species nature. Future assessments may refine to focus on fewer key species or incorporate better data collection.

Non-Commercial and Charter Fisheries

Most fishing on Guam is non-commercial, supporting food security, cultural practices, and recreation. While non-commercial effort is largely pelagic trolling, bottomfishing, spearfishing, and shorefishing are also important. Guam’s charter sector serves residents and visitors (including from Japan, South Korea, and the United States Armed Forces) and mainly trolls for blue marlin, skipjack, and mahimahi, with some trips also targeting bottomfish.

Crustaceans Ecosystem Components

There were no federal permit holders in Guam for lobster or shrimp in 2024.

Precious Corals Ecosystem Components

A federal permit is required for anyone harvesting or landing black, bamboo, pink, red or gold corals in the exclusive economic zone (EEZ) in the US Western Pacific Region. No precious coral or special coral reef fishery permits have been issued for the EEZ around Guam since 2007.

Ecosystem Components

National Standard 1 allows for the Regional Fishery Management Councils to identify species, species complexes, and stocks that would constitute Ecosystem Components (81 FR 71858, October 18, 2016). Ecosystem Component Species (ECS) contribute to the ecological functions of the island fisheries ecosystem. These species are retained in the Mariana Archipelago FEP for monitoring (rather than ACL management), recognizing their important ecological role and supporting efforts to address broader ecosystem concerns.

Coral Reef Ecosystem Components

Hook and line is the most common method of fishing for coral reef fish on Guam, accounting for around 70-75% of fishers and gear. Throw net (talaya) is the second most common method accounting for about 10%. Other methods include gill net, snorkel spearfishing, surround net, drag net, hooks, gaffs and gleaning. Less than 20% of the total coral reef resources harvested in Guam are taken from federal waters (3 to 200 miles from shore), primarily because the reefs in the EEZ are often associated with less accessible offshore banks. SCUBA spearfishing became illegal in May 2020 when the Guam Legislature passed Bill 53-35.

In 2024, the top 10 ECS in Guam’s boat-based creel survey were led by assorted reef fish (23,722 lbs) and bigeye scad/atulai (11,020 lbs); the top 10 combined totaled 52,453 lbs and also included bluespine unicornfish (4,911 lbs) and deep bottomfish (4,735 lbs). The Guam Division of Aquatic and Wildlife Resources also identified nine priority ECS for regular monitoring; in 2024, most priority ECS catches were below their 10- and 20-year averages, except bluespine unicornfish (4,911 lbs; +2% vs. 10-year avg, –4% vs. 20-year avg) and longface emperor (1,972 lbs; +139% vs. 10-year avg, +111% vs. 20-year avg).

Fishery Issues

Guam fisheries are dynamic and always changing. Explore the key Guam and Mariana Archipelago issues the Council is addressing.

Fishery Ecosystem Plans

The Western Pacific Regional Fishery Management Council, under authority of the Magnuson-Stevens Fishery Conservation and Management Act, creates and amends management plans for fisheries seaward of state/territorial waters in the US Pacific Islands. The Western Pacific Council’s Fishery Ecosystem Plans (FEPs) are place-based and utilize an ecosystem approach. An overall Pacific Pelagic FEP was created because of the migratory nature of the pelagic species. Both the Mariana Archipelago (CNMI and Guam) and Pelagic FEPs were approved in 2009 and codified in 2010. These FEPs are amended as necessary.

Ecosystems + Habitat

Regulations + Enforcement

Protected Species

Quotas + Annual Catch Limits

Marine Conservation Plans

Marine Conservation Plans (MCPs) are required by the Magnuson-Stevens Fishery Conservation and Management Act (Section 204(4)) detailing the use of funds collected by the Secretary of Commerce pursuant to fishery agreements (e.g., Pacific Insular Area fishery agreement, quota transfer agreement, etc.). Plans should be consistent with the Council’s Fishery Ecosystem Plan, identify conservation and management objectives, and prioritize planned marine conservation projects. MCPs are developed by the Governor of each territory and are applicable for three years.

Projects and Publications

The Council has done a lot of work in Guam fisheries from research, to workshops, to outreach and education. Below are some of the completed projects and publications.

- WPRFMC. January 2016. Fishing Conflicts on Guam- A Report of Meetings and Interviews with Fishermen. Honolulu

- Pacific Coastal Research and Planning. 2016. Mapping the Coral Reef Fisheries of the Mariana Islands. Honolulu.

- Kyota, C. May 2015. UOG Rabbitfish Manahak Project 2014-2015

- Bak, S. November 2014. Guam Naval Base Data Collection Program 2013-2014

- Council staff. 2014. Territorial fisheries staff issues and needs

- Bak, S. February 2012. Evaluation of Creel Survey Program in the Western Pacific Region (Guam, CNMI and American Samoa)

- Walker R, Ballou L and Wolfford B. Non-Commercial Coral Reef Fishery Assessments for the Western Pacific Region

- Luck, D., & Dalzell, P. (2010). Western Pacific Region Reef Fish Trends: A Compendium of Ecological and Fishery Statistics for Reef Fishes in American Samoa, Hawai’i and the Mariana Archipelago in Support of Annual Catch Limit (ACL) Implementation (Tech.). Honolulu, HI: Western Pacific Regional Fishery Management Council.

- Luck & Dalzell Appendices

- Lucas and Lincoln. 2010. Impact of MPAs on Guam Fishermen Safety

- Miller et al. 2001. Proceedings of the 1998 Pacific Island Gamefish Symposium: Facing the Challenges of Resource Conservation, Sustainable Development, and the Sportfishing Ethic. (29 July-1 August 1998, Kailua-Kona, Hawaii, USA)

- Amesbury, J. 1989. Native Fishing Rights and Limited Entry in Guam.

Indigenous Resources

Since time immemorial (manåmko’ na tiempo / desde tiempom antes), CHamoru communities have lived in profound reciprocity with the tåsi (ocean)—as a living ancestor, provider, teacher, and sacred relative. The ocean sustains nourishment, spiritual connection, cultural identity, and intergenerational continuity.

CHamoru traditional ecological knowledge (tinanom / ancestral wisdom) guides sustainable practices, including lunar and seasonal observations, selective harvesting, and communal sharing (fanachå’an) that strengthens social bonds and equity. Traditional methods—such as net fishing, spearfishing, and seasonal harvesting—reflect knowledge passed through generations to support abundance and stewardship.

Indigenous fishing continues to strengthen cultural heritage and community resilience, supporting food security and maintaining connections to cultural knowledge amid modern pressures. Protecting these practices is essential to sustaining Guam’s identity and ensuring future generations can continue to live in harmony with the sea.